Creative people are in demand in the workplace and the good news is that you don’t need to be in full-time employment to be a part of it.

Freelancing is an alternative that gives you the flexibility to create work that speaks to your values without committing to any one organisation.

This guide, produced by creative freelance professionals, explores how your skills can be positioned in the market, where your clients might be found, and what the steps you need to work through are.

Expand each point and use it as an ongoing plan to launch your freelance career with confidence!

1. Approach your career as ‘the journey of a lifetime’

Freelancing and self-employment are the mode of travel that most creatives will activate many times over a creative lifetime to support their creative practice, professional goals and business aspirations.

As creative people, we are committed for the long haul, mainly because creativity is in our DNA; we are compelled by it and we have been trained to use it.

So learning from others ahead of us, we see that a creative career is best approached as “the journey of a lifetime” with many opportunities for success, failure and challenges along the way.

What is the “Journey of a Lifetime”?

Download the illustration of the “Journey of a Lifetime”.

The inner ring is YOU – this is where your vision, courage, insights and determination shape who you are as a creative professional.

The outer circle drives those decisions and each one of the four creative skills sets – Financial Know-how, Communication, Networks and Collaboration – is crucial to your success as a creative on ‘the journey of a lifetime’. Each has many professional and technical things to get a handle on as your creative career develops and grows as you’ll see in the lists accompanying each skill set.

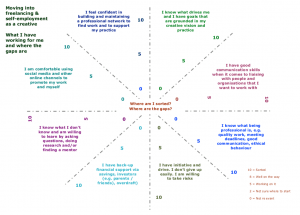

2. Check your readiness to begin freelancing

This “radar” exercise will help you to understand the attributes of a successful freelancer, which areas you feel confident about and those areas you need to work on.

Download the ‘radar’ template and work your way around the diagram marking how you rank your current skills in each area using the scale provided on the diagram.

Then, draw a line around the diagram to join each of your dot points to create an overall shape that represents your current situation – and where to focus your professional or skills development efforts in order to strengthen your readiness to take up freelancing or self-employment.

As you work through the remaining steps, be sure to look for action points in the areas you have identified where you need further learning. In future, you can return to this exercise to reassess and see your growth in those areas.

3. Tap into your existing skills and experience. What personal resources do you already have?

To begin building your personal platform, use the resources you already have at your disposal. These are the things that make you unique – your skills, experiences, specialist knowledge and connections.

Create a list or make a visual picture of your personal platform using the questions below to stimulate your thinking.

Photo by Clarisse Croset on Unsplash

1. What skills do you have? (E.g. you have experience running school holiday programmes; you know how to make things; you have strong digital skills; you know how to code).

2. Who do you have in your network? (E.g. your Aunt runs an organisation in the creative sector; your brother is connected to a primary school; your best friend is in a professional network in the business sector).

3. What other resources do you have access to? (E.g. you have studio space, tools and/or equipment; you have a mentor or coach; you know people who can help)

4. What are your hobbies? (E.g. now and in the past)

5. What clubs have you been a part of? (E.g. Juggling Club; kapa haka; meet-up groups).

4. Know what motivates you, especially when the going gets tough

Your motivation, or your “why” is what will keep you going through the tough times. It’s what will get you out of bed in the morning. It’s your passion, purpose and drive.

What do you care about with energy and passion? Create a list of the people, situations and/or things that motivate and inspire you. Add as many items as you can think of prompted by these questions:

Photo by Nikita Kachanovsky on Unsplash

1. What things do you care about? (E.g. homelessness, animal welfare, contemporary music, tikanga Māori, community gardens)

2. Who inspires you? Why? (E.g. friend who is a climate activist; teacher (secondary school and/or university;) family member who works in the community)

3. What activities get you into creative flow so that time vanishes? (E.g. dancing, drawing, reading, skateboarding, travelling)

4. What have you volunteered for? (E.g. Trade Aid volunteer; street collector for community organisation; local school; environmental organisation)

5. If you never had to work, how would you spend your time? (E.g. travelling, making art, being of service to my community, starting a business).

5. Describe how your skill-set could help solve a problem in the world right now

Skills and ‘why’ are not enough – you also need to offer value to other people by applying your skills in a useful way.

One way of doing this is to go “problem-finding” as your opportunities may lie in your ability to help solve a problem for someone, an organisation, a community and/or a place. Where are the challenges, situations and openings into which you could contribute your creativity, ideas and skills?

Create a list of needs you could address, and add as many items as you can, prompted by these questions:

Photo by Ian Schneider on Unsplash

1. What things do friends and family ask you to help with?

2. What do you think is missing from your local community?

3. What problems do you see your friends experiencing daily?

4. What really annoys you about the world?

5. What does the world need right now?

6. Create ‘rough & ready’ profiles to describe several people who are working on problems that resonate with your skills and interests

These people represent your potential customers. They’re specific people (or made-up characters representing your future customers) you could work with or sell your offerings to.

We cannot sell something to ANYBODY, so the more we can describe the characteristics of potential customers and clients, the better.

As a starting point, you may be thinking of an organisation in the public or private sector. Using online research, identify a person in the organisation that seems to be connected to the type of work that you want to do.

Use the questions below to identify three different customer ‘avatars’ that you could sell to. Then identify as many of the demographics about them as you can – the more specific the better! Download the avatars handout if you would like a template to work with for this exercise.

Prompts to help you think of some potential customers:

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

1. Who has paid you for something in the past?

2. Who has shown interest in your professional offerings, creative ideas or tangible skills?

3. Who do you think NEEDs what you have to offer; (e.g. who has shown that they have a problem/need you can help with)?

4. Who have you helped in the past using your skills (and this may have been unpaid)?

5. Who do you WANT to help?

6. Who would you LOVE to work with or help?

Once you have three customers identified, for each one note these details and demographics using the template:

Photo Credit: BRICK 101 Flickr via Wunderstock

1. Person’s name (make one up as need be)

2. Name of organisation that they are connected to (if relevant)

3. Age

4. Gender

5. Location (i.e. country/city/suburb)

6. Industry sector

7. Employment status (i.e. role)

8. Revenue information (for the person: income or organisation: turnover)

9. What the person or organisation cares about (i.e. use LinkedIn or other online research)

10. What the problems are in a work context that you could help with

11. Other people who are similar to the person and/or organisation – in Auckland, in New Zealand, internationally

7. Find a person in your network who can introduce you to someone who fits one of your profiles

This is where you start to activate your network of connections.

Looking back at the personal skills and resources you identified in Step 3, who do you know who knows a person or organisation that fits one of the profiles you have created? Who do you know who seems to have a problem that your skillset could help to solve?

Photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash

Talk to your contact. People like to help other people, so if you share with your contact a little about your motivation and ask politely for an introduction to the person or organisation that fits your target profile, they will probably be happy to do that for you. It can be as simple as an email introduction.

Make sure you follow up and thank your contact and don’t forget to let them know in the future what happened.

When you are introduced, reach out to the new person by providing a brief introduction to yourself including asking if could shout them a coffee to discuss how you might work together.

8. Connect with your potential customer to find out as much as you can about them

The most critical part of finding a client or a specific market to connect with is the conversations that you have with people who represent the market, organisation or situation that you are wanting to offer your skills, services and/or products.

Photo by Adam Solomon on Unsplash

Now that you have a connection with a potential new customer who aligns to one of the profiles you have created, find out as much as you can about them including what needs, gaps or challenges they have.

While they might have some solutions in mind already, do your best to thoroughly understand the problem, so that you can later consider how the skills and resources you have at your disposal can best be used to help.

Even if this meeting doesn’t turn into a paying customer, what you learn about the issue and the market will be useful if you need to move on to another connection and opportunity.

9. Articulate how you can contribute to solving their problem

When you approach a prospective client in this way, be sure to write a thank you email and include a sentence or two that describes what you heard the prospective client say about a gap, need or challenge that they have.

If it feels right to do so, you could also provide a short description of how you could help the prospective client bridge a gap, fulfill a need or move forward on a challenge. Then it’s a case of waiting to see what response you receive.

That response may include an invitation to meet again or in some instances the prospective client may send you an outline of the job or project that they would like to consider you for, along with information about what they would like from you next. That could be a response to a work brief, a cost estimate, a fee for services quote or a design concept.

10. Put a price on the value of your contribution

Knowing what to charge is one of the biggest mysteries for freelancers starting out.

Asking around to get an understanding of the fees being charged for services and products similar to your own is a useful habit. Keep an eye on industry bulletins and magazines, even the business pages of various newspapers as it’s surprising where information about what people are charging is found. This type of informal research will help you to understand how you are positioning yourself in the marketplace.

Be willing to talk about what you charge when you’re asked to help build a culture of honesty about money.

The creative sector is notoriously underfunded and this reputation can be self-perpetuating. If you believe there is little or no money in the arts sector for example, then your perception is that your skills and services have little value and you are more likely to undercut your own pricing.

11. Know the cost of doing business

As a freelancer or self-employed contractor, there are certain benefits you won’t receive when you undertake paid work that you can expect as an employee of an organisation. (Read more about the difference between an employee and a contractor here).

For example, you will be responsible for collecting your own personal income tax and paying that to Inland Revenue (IRD). You will also need to pay an annual levy to Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC).

As you are self-employed you will not be required to pay into KiwiSaver. It is strongly recommended nonetheless that you set up a KiwiSaver account with a provider of your choice in order to receive the New Zealand Government’s annual contribution to your account. See the KiwiSaver website for further details.

Photo by Acharaporn Kamornboonyarush from Pexels

For many reasons, it’s important to understand the costs involved in producing your work or delivering a creative service.

The starting point is to create a budget of your operating expenses. What is the cost to you of being in business as a freelancer or someone who is self-employed?

Here is a list of things to factor in when you get started:

- Accounting & bookkeeping services

- IRD and ACC obligations

- Annual contribution to KiwiSaver

- Entertainment (e.g. coffee meetings)

- Holidays: How many days of holiday will you take annually?

- Insurances – The insurances listed below may not be necessary when you are starting out. However, it is recommended that you review your insurance portfolio at least once a year.

- Public Liability (Protects you and your business against various financial implications if you are found liable for loss or damage to other people’s property, or cause illness or injury that is not covered by ACC)

- Professional Indemnity (Designed for professionals who provide advice or a service to their clients. If someone alleges that you’ve made a mistake, overlooked a critical piece of information, misstated a fact or they have misinterpreted you in the course of your work resulting in a financial loss for your client, they may take legal action against you to recover those losses)

- Income Protection (Pays a monthly benefit to you if you are unable to work in your own occupation due to illness or injury)

- Internet connection

- Legal services (e.g. advice about intellectual property)

- Marketing, promotion and advertising including the time spent doing this work if you do it yourself

- Meetings: client/team/project

- Postage and shipping

- Printing and copying

- Office and/or studio and/or hot-desk

- Online subscriptions (for tools, platforms etc.)

- Special equipment as required by your field or discipline

- Local and/or international travel

- Utilities: electricity, gas, water

- Vehicle expenses: e.g. a portion of your petrol and maintenance costs

- Parking

- Your professional development: consider how much you would like to set aside on an annual basis to up skill yourself

- Website costs: hosting, domain registration etc.

Once you have a good understanding of how much it costs for you to be in business, you know how much you need to make in order to break even to cover your costs. To this figure, add your labour costs (based on an hourly rate) and then a small profit margin.

Use the Cost of Doing Business Calculator to help you figure out what your gross annual income goals should be to cover your costs. The calculator has been produced for independent photojournalists and is easily adapted for other creatives, such as you.

12. Get comfortable about charging for your work

When you know how much money you need to make annually to cover your work-related costs, your hourly labour rate and a small profit margin, you can approach pricing your product, project or proposal. There are many options. Here are two: 1. Charging an hourly rate and 2. Setting a project fee.

Establishing your hourly rate

Here’s one method you can use to set your hourly rate:

1. Work out the number of workdays you have available in a year once you have deducted days for holidays, sick leave, training and working on your own business. Note: You can also choose a month, 12-week or six-month period instead of one year.

2. Assuming that your typical workday is six hours (remember work/life balance) multiply the number of workdays that you have available a year by six hours (or the number of hours per day that you’re planning to be engaged in work that you expect to be paid for) to get the total number of hours that you have available for paid work in one year. This is what is known as billable hours, noting that as the year unfolds you may not be able to invoice for some of those hours due to circumstances beyond your control. Write the number of billable hours on a piece of paper.

3. Using the Cost of Doing Business Calculator (see step 11), write down the total cost of ‘doing business for the year’. This dollar amount includes expenses, income tax, a small profit and the annual salary that you want to pay yourself. Note: To calculate your income tax, use the calculator available at paye.net.nz. Write the total cost of doing business for the year as a dollar amount next to the billable hours.

4. Now divide the dollar amount by the billable hours to calculate your hourly rate.

Over the year, you may tweak this rate based on what you have learned about the costs of similar services being offered by other creatives but in doing so be aware how this will affect your ability to pay your work related costs and/or your profit margin.

Here two examples:

—

Example #1:

1. Number of work days available over one year: 220 (being five days a week for eleven months of the year)

2. Number of chargeable hours in each workday (on average): 4 hours (or 20 hours per week). Total number of billable hours per year: 880 hours

3. Total “cost of doing business”: Expenses (e.g. $500 per month costs plus ACC levy of $695): $6,195. Income tax: $8,020. Labour: $50,000. Profit: $4,400. TOTAL: $68,615

4. Hourly rate: $77.97 Note: if the profit margin is removed, the hourly rate is: $72.97

—

Example #2:

1. Number of work days available over one year: 132 (being three days a week for eleven months of the year).

2. Number of chargeable hours in each workday (on average): 5 hours. Total number of billable hours per year: 660 hours

3. Total “cost of doing business”: Expenses (e.g. $300 per month costs, plus ACC levy of $625.50): $3,925.50. Income tax: $6,505. Labour: $35,000. Profit: $2,500. TOTAL: $47,930.50

4. Hourly rate: $72.62. Note: if the profit margin is removed, the hourly rate is: $68.83

—

Whether you choose to disclose your hourly rate to your client is up to you and the situation. Understanding your hourly rate empowers you to decide with confidence about how to manage charging for your time either by the hour or as an expenses line in a project budget.

Project rates

A project rate is an agreed price that you negotiate with a client to undertake a project. It is usually a fixed amount that includes all project costs including labour.

In order to find a project rate that covers your time and other resources that you provide to the project, first consider how much time availability you have and what percentage of that “productive” availability will be dedicated to the project on a daily, weekly and/or monthly basis.

Example: If it’s a big project and you will be working on it entirely for 50 percent of your productive time over three months, you know you need to charge 50 percent of your operating costs as well as your labour costs.

Consider that:

- Committing to a large project might mean your client supplies some operational resources that you no longer need to account for

- You may not be working as much on marketing and promotion and thus don’t need to include that cost

- The unexpected will happen so consider adding a 15 percent contingency to your estimate to account for overruns.

“The reality is, when you are making, there’s a lot of work that happens behind the scenes that clients don’t necessarily see. All the brainstorming and internal rounds of design you did, or the drafts of copywriting, before having work to present.

My preference has always been never to reveal an hourly rate but to work on a project rate instead. Project-based pricing means looking at the project as a whole, scoping it — usually with the client — and then putting a price and timeline on it. In this scenario, you and the client are looking at the overall value that is being delivered instead of an hourly, line-by-line setup.”

– Jess Eddy, excerpt from 15 secrets and tips to set you up for massive freelance success published on Medium, September 2018

Value based pricing

Pricing based on the value of your work takes into account your costs including hourly labour rate but other factors too such as:

- What your work is worth in the marketplace (e.g. the service is in high demand and thus more expensive; or if you are in a saturated market, i.e. there are lots of creatives offering the same type of service, it may be the opposite)

- The value of your work to the client and what they are willing to pay to benefit from that value

- The alignment of your values and motivations with those of your client; for example you may be willing to charge less for your services to a client working in a sector you wish to break into or tackling an issue close to your heart

- Remember that the price you set also informs the perception of value by the client. A $500 service will be expected to be of lesser value than a $3,000 one, but remember you must justify the value of your contribution.

Example: You are offering to develop a jingle for a client, while your client can license an existing tune elsewhere for $100. You are planning to charge $650 for the service because you are composing and recording a bespoke piece of music for the client to their specifications.

You can justify the additional expense because unlike the other option, you are including the bespoke composition of the music for your client and licensing it to them for exclusive use.

You are solving the client’s problem more effectively, and so providing greater value.

Remember that sometimes a client will opt for a solution that costs more because their perception of the quality of that product or service is higher.

13. Present your proposal

Prepared with a confident understanding of the problem that you are helping a client to solve and how you can assist through the services you propose to provide alongside the fee you plan to charge for your work, it’s time to put forward your proposal to your client.

Your proposal may be in the form of a quote or a more detailed brief to be sent electronically. If your proposal (quote or brief) is to be sent as a PDF attachment to an email, be sure to promote yourself using a distinctive letterhead.

When preparing a proposal, it’s worth remembering that you are creating value for your client or customer. We love this excerpt from (and indeed the whole article) 21 Insights from 21 Years as a Creative Coach, by Mark McGuinness.

Stop ‘earning money’ – start creating value (Insight #17)

You create your own reality through the words you speak, the words you write, and even the words you think to yourself. As long as you tell yourself you ‘have to earn money’, you are living in a world of hard work, drudgery and suffering. Money is tied to effort. So it feels somehow wrong to earn it without putting in a lot of effort. And you can easily – and mistakenly – assume that simply working harder will bring you more money.

But if you forget about earning money and focus on creating value, you enter a different world. A world where your income is not tied to the effort you put in, but to the value (emotional, experiential, practical, financial) you create for others. A world where a single painting can be sold for millions of dollars, where a single song can touch millions of hearts, or a single book can change millions of lives.

One of the many wonderful things about being a creative is that there is virtually no limit to the value you can create for others, and therefore potentially no limit on the money you can generate. Just look at the money created by the most successful painters, designers, actors, musicians, authors, architects, entrepreneurs and other creatives.

So forget about ‘earning money,’ it feels too much like drudgery. It’s also too selfish, because it’s all about you – your effort, your money. Instead, focus on creating value – a.k.a. what you can do for others.

Include in your proposal a summary of the client’s problem, how you plan to contribute your skills to addressing that problem and all of the things that are included in the fee. Also include a list of the tangible outputs that you will deliver and a calendar of milestones and/or key dates so that the client knows what will be delivered when.

If there are elements related to the project that you have NOT included in the fee, or if there is a risk the client may assume certain items have been included, list them as exclusions. For example, excluding travel anywhere other than the stated place of work or engagement, or excluding handing over source material for your end product.

Remember, a proposal could be as simple as an email, a “one-pager”, or for a more complex project a multi-page document or presentation.

14. Negotiate the terms of your engagement. How will you work together?

Some details that may or may not have been in your proposal could need to be negotiated before your client agrees to the project.

Photo by Cytonn Photography on Unsplash

Your client may wish to include some line items you have excluded, or you may need to agree how the work you do will be supported or continued once you have left the project.

Once a client has accepted your proposal, a “Terms of Engagement” document, for example in the form of a letter (PDF) signed by both parties is a useful way to set out these expectations and agree on them. Such a document specifies the agreed place of work, the project budget (as set out in the proposal including labour costs) and any additional items not covered in the proposal.

Think of this document as a freelancer’s version of an employee’s Employment Agreement.

Remember to sign this contract, and have your client do the same.

15. Get to work, get paid!

Your client has agreed to hire you and a Terms of Engagement document has been signed by both parties – great! It’s time to get on with delivery.

Depending on the project, you may have agreed on project meetings and updates, but remember to keep your client informed on your progress where relevant. How you bill for your work will depend on the payment model you choose.

Deposit – “% upfront”

A deposit model is most common where you have agreed to a price that covers the whole of the project’s delivery. Two options are:

1. One-third payment at the signing of Terms of Engagement document; one-third at the halfway point of the project once an update report has been submitted to the client, and a final third when the project has been signed off as completed by the client.

2. Fifty percent of the project fee when the Terms of Engagement document is signed, and the remaining fifty percent when the project is signed off as completed by the client.

Both these models are useful to ensure you have capital to invest in the supplies and resources you need to complete the work required to deliver the project successfully.

Monthly billing

Monthly billing is where a provider or vendor (that’s you) issues an invoice every month for work completed within that month. This method can be used even if you have agreed to an overall project cost. The monthly billing schedule is set out in the Terms of Engagement so that your client and you can plan for cash flow. What you bill for monthly should reflect the work that you have undertaken and delivered month to month.

If you do choose to bill hourly, you may issue this monthly invoice for hours completed in the same billing month. Usually an invoice is itemised and lists the services or supplies provided and their individual costs as line items. Agreed expenses excluding GST are also listed as line items on the invoice.

What else to include on your invoice

Your invoice must include the following:

- The words: Tax Invoice

- The date of issue

- The client’s business name and address

- Your business name and address

- An invoice number

- Your GST number if you are registered for GST.

After income of $60,000 per financial year in New Zealand, you are obligated to pay GST (Goods and Services Tax) of 15 percent to the Inland Revenue Department. GST is added as a final line item on your invoice and is calculated once you have a total figure for all the other line items listed in the invoice. Multiply this total figure by .15 to find the GST for this invoice, and add to the invoice total to be paid by the client to you. - Payment Methods

The methods of payment you offer should be clear. Most commonly and simply you can add your bank details and instructions to the bottom of the invoice, plus any pertinent payment information such as what reference number your client should include with the deposit. - Payment Terms

Some businesses in New Zealand make and expect payment on the 20th of the month following the date of issue of an invoice. However you can specify on your invoice what the payment delivery terms are that you expect, for example, 10 business days. Even if this is set in your Terms of Engagement, it’s worth noting again on the invoice which may be handled by an accounts department.

This material was developed for the workshop “Your opportunity as a freelancer”, delivered in CDES’ Workshop 101 on Saturday, 19 October 2019. The resources have been adapted for you to use independently.

If you’d like to get more in depth exploring your skills and experience leading into your career, CDES have a module available on finding your career path which also goes into more depth on this: